Trust Plus: Why ‘Too Much’ Trust Can Hurt Innovation

Most of us believe that trust and innovation rise together. It seems intuitive that the more comfortable we become with our collaborators, the more likely we are to voice risky ideas or take creative leaps. Trust creates conditions for risk-taking, familiarity enables vulnerability, and shared understanding should speed up progress.

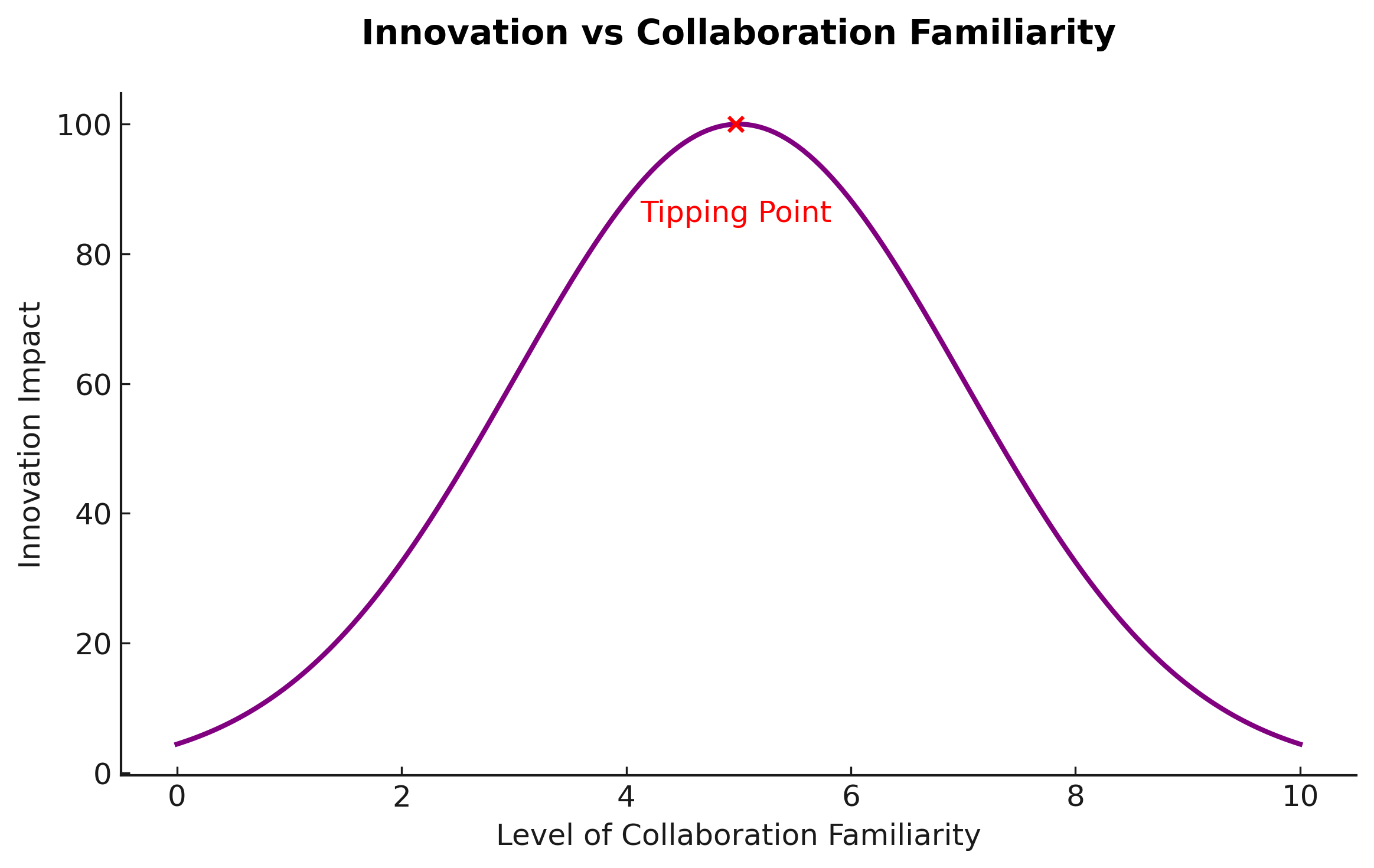

Research suggests this relationship is more complex than we might expect. Studies across multiple fields show that after people work together for a period of time, there's a tipping point at which innovation actually begins to decline, even as trust continues to grow.

The Collaboration Curve We Don't Discuss

Research tracking thousands of patents over decades reveals something counterintuitive about long-term collaboration. Teams do show increasing innovation impact through their first several collaborations, but the data reveals a clear pattern: after that initial period, the innovation impact of their work begins to decline.

The very relationships that initially fueled creativity eventually began to constrain it.

This pattern appears beyond patent research. A study of Broadway musicals found similar results, highlighting what researchers call the "small world network" problem. Teams with moderate levels of repeat collaboration (a mix of familiar and new relationships) produced the most successful shows. A balance of continuity and freshness proved more powerful than either all-new or overly familiar teams.

When Comfort Becomes the Enemy of Innovation

Why does this happen? When teams work together repeatedly, they develop cognitive entrenchment - falling into familiar patterns of thinking, established ways of approaching problems, and comfortable assumptions about what will and won't work.

Research in organisational psychology shows that teams can slip into groupthink, where highly cohesive groups prioritise harmony over critical evaluation. This makes them less likely to welcome dissenting perspectives or consider alternative approaches.

The trust and cohesion that once enabled risk-taking can actually start to reduce it.

The Network Science of Innovation

Network research provides insight into why fresh connections matter. Research shows that people who bridge different groups tend to generate more innovative ideas. Research across multiple industries found that managers with networks spanning different clusters were more likely to have ideas rated as valuable by senior executives.

Similarly, research on entrepreneurial teams found that founders with more diverse social networks were more likely to develop novel business models. Teams drawing from homogeneous networks showed much lower rates of innovation, even when they had high levels of internal trust and collaboration efficiency.

Innovation thrives at the intersection of different knowledge domains. Breakthrough innovations typically occur when concepts from one field collide with insights from another.

The Antidote: Strategic Unfamiliarity

Teams that maintained their innovative edge had one thing in common across multiple studies - they regularly introduced new elements to their collaborations.

Mitigation strategies can include both idea diversity (bringing in insights from different fields) and contributor diversity (bringing in new people and perspectives) to counteract the decline in innovation that results from repeated collaboration.

A study from Harvard Business School showed that certain scientific problems were more likely to be solved by people from outside the relevant field than by domain experts. Outsiders brought fresh perspectives that weren't constrained by the field's conventional assumptions. (Interestingly, the study also highlighted not just field of expertise but other types of ‘outsider status’ as improving outcomes, noting that “Female solvers – known to be in the “outer circle” of the scientific establishment - performed significantly better than men in developing successful solutions”).

Research on innovation in design firms showed that the most creative solutions came from teams that could recombine knowledge from different projects and industries.

Practical Applications

Recognising the reality of the intersection of trust and innovation doesn't require dramatic overhauls. Even modest changes can help:

Adding a newcomer can shift how teams share knowledge and solve problems

Simply asking teams to consider how outsiders might view their challenges can boost creative output

Seeking out learnings from outside our field or network can stimulate new thinking

Brief presentations or analogies from other fields can generate new solution pathways

The goal isn't to import chaos into trusted collaborations but to inject just enough unfamiliarity to keep thinking sharp and the innovation trajectory rising rather than plateauing.

Trust Plus

Trust remains essential for innovation—it just can't sustain innovation alone. Once you reach the tipping point of familiarity, you need what we might call "trust plus."

The most effective teams combine psychological safety with high standards and intellectual challenge. They create environments where people feel safe to take risks while ensuring those risks push beyond familiar territory.

Your most trusted collaborators might also be your most limiting ones - not because they're not good enough, but because you've become too good at thinking the same way together, or have too many shared reference points.

The question becomes: How do you keep the trust but add strategic unfamiliarity? How do you keep new ideas, new learnings, and new voices flowing into your teams and collaborations?

Because while trust enables execution, it's the productive discomfort of fresh perspectives that fuels breakthrough thinking.